Hi it’s Ben and Charlotte, welcome to The Entmoot.

In this week’s issue we'll look at:

The Climate Change Committee recommends that the UK reduce emissions by 81%

UK zoo welcomes two red panda cubs

Latest job posts

And more…

Best links

Wildlife Conservation

Species spotlight - Huemul (Forbes)

Northern Ireland’s wildlife faces “unsustainable” pressure (Birdguides)

Climate Change

Lab using bee’s honey to learn more about climate change (BBC)

Climate Change committee recommends that the UK reduce emissions by 81% (Energylivenews)

Zoo news

Zoo welcomes two red panda cubs (BBC)

Zoo helps global conservation efforts with key data (themoorlander)

Botany

Missouri names first female president of Botanical Gardens (Spectrum news)

Jobs

Zoo keeper positions are available at Exmoor Zoo, New Forest Wildlife Park and London Zoo (BIAZA)

Find the latest environmental, Ecology, and fundraising positions here (Environmental jobs)

Featured Article - Halloween special

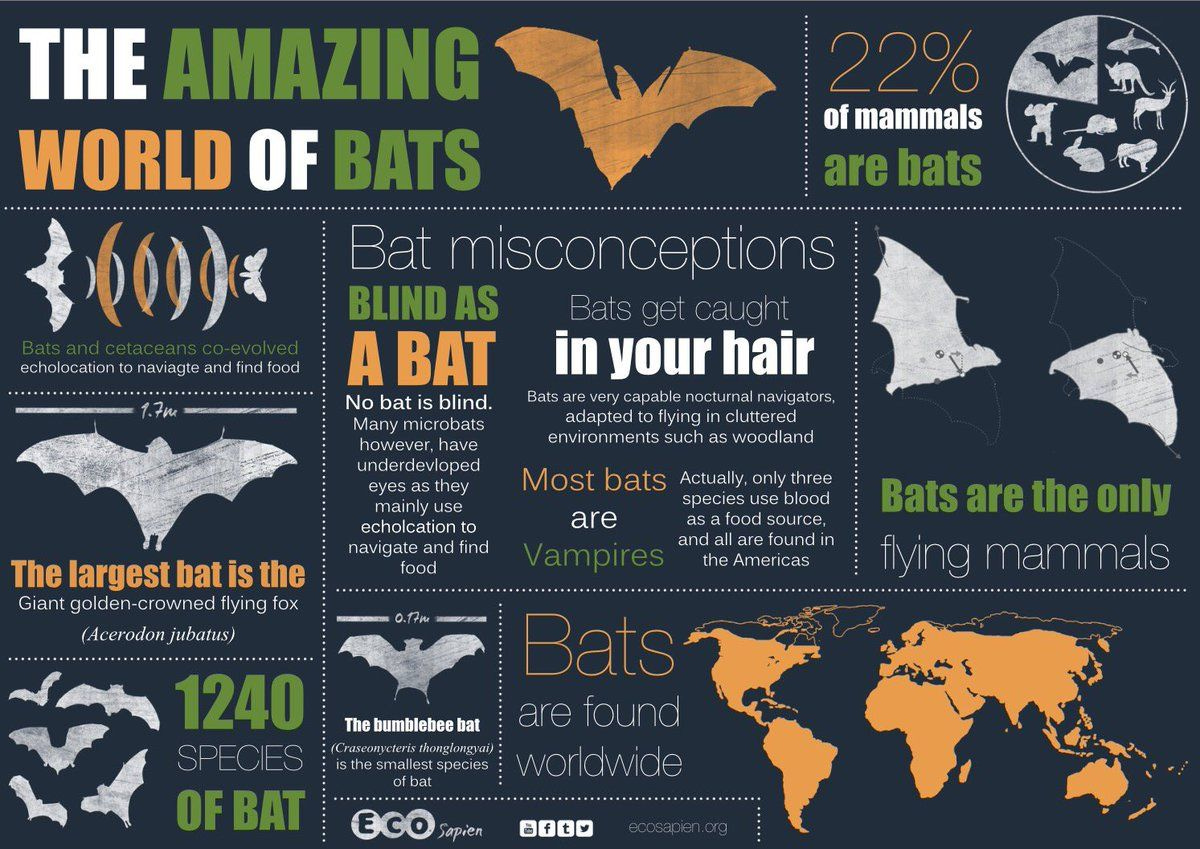

There are over 1,400 species of bats across the world, making up around one-fifth of all mammals on earth and being the second biggest order behind rodents. They can be found on almost every continent, and have diversified to fit into a great variety of ecosystems.

Despite being so widespread and such an important species, many people have a negative opinion of bats - their association with the occult, reputation for spreading disease, and their mysterious nocturnal nature have led many people to fear them. But bats are everywhere, and they have a significant impact on the habitats they live within. So, for Halloween, let’s take a look at what bats are, what they do and why they are important to look after.

Bats can be quite diverse in their morphology and behaviour, however they all possess some shared characteristics. They all have wings and are the only true flying mammals, all roost in large numbers, all give birth to live young, and (nearly all) are one of a select few animals that use echolocation.

They range greatly in size, from the adorably tiny bumblebee bat, to ‘giant’ flying foxes that can have a wingspan of up to 5 feet across. Their diets are well-adapted and diverse, and can consist of insects, fruits, fungi, nectar, small reptiles, birds and rodents.

Bats are thought to have a greater diversity in mating systems than any other mammal and have been known to form varying types of reproductive relationships. Most species however are thought to be polygamous, with one or two males forming harems and mating with multiple females.

Evolution

Bat evolution is a mystery, as their delicate skeletons do not fossilise well. The earliest record of a bat-like ancestor we have is believed to have already had flight, so it is unknown exactly how this trait evolved in a mammal. It is hypothesised that the common ancestor of bats was an arboreal mammal that evolved first to glide and then to fly, but due to the large gap in the fossil record, it is not clear how long this transition took.

It was also proven that this early bat did not have the ability to use echolocation, and instead relied on sight and smell to hunt prey, giving even more reason to believe that this species inhabited forested areas.

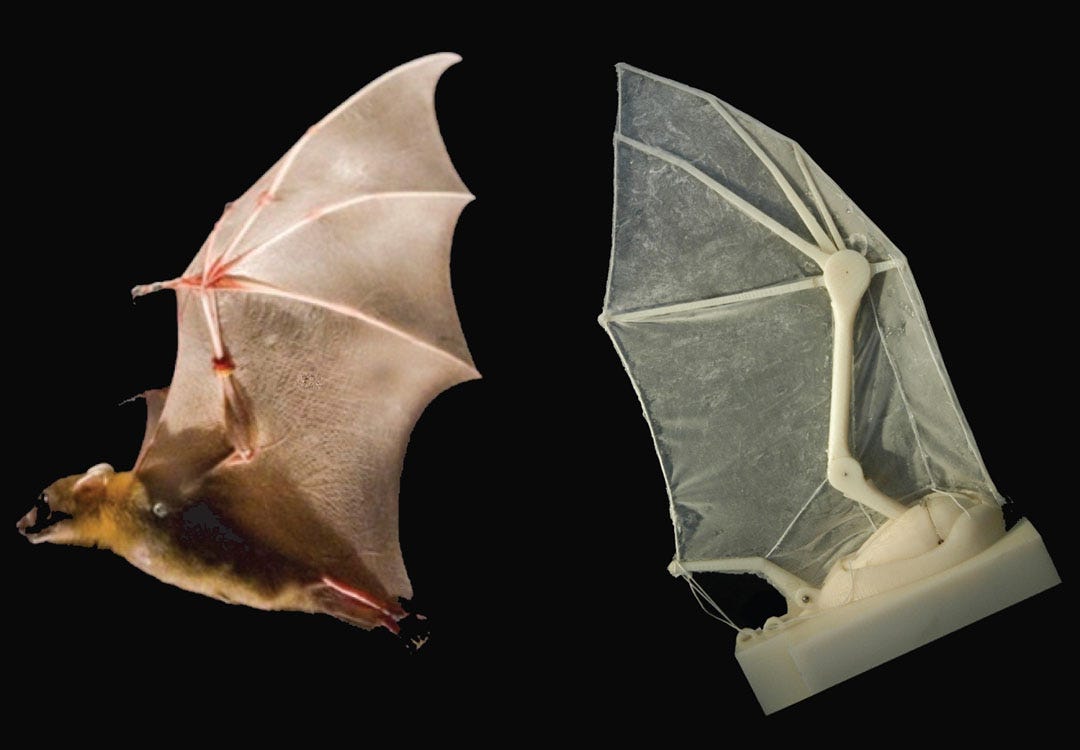

By looking closely at their anatomy, we can see that a bat’s wing is actually a highly specialised hand - individual digits are present, including the equivalent of a thumb, and very thin skin has formed webbing to connect them and allow bats to take flight.

When we look at another group of animals that have developed flight - birds - we can see some big differences in how they are adapted for life off the ground.

Birds have evolved to offset their sometimes huge size by becoming as lightweight as possible; they have hollow bones filled with air pockets, lay eggs so females don’t have to fly while pregnant, and concentrate their waste into a single solid, rather than filling their bladder with heavy urine that would weigh them down.

Bats in comparison have dense mammalian bones, give birth to live young, and have typical urine and faecal secretion. Unlike birds, bats have remained small, and while there are some larger species, they don’t come close to the size of the largest birds. By staying small, bats have mitigated their heavier characteristics to allow them to fly.

Bats have been able to remain small because they have filled niches that require them to be. They aren’t major predators - the smaller species of bats are mainly insectivores, while some feed on nectar, small reptiles, rodents and birds, therefore needing to be light and agile. The largest bats are frugivores that do not need to catch prey and can afford to be larger and heavier.

Echolocation

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of bats is their use of echolocation. Around 70% of bats deploy this technique for hunting and ‘seeing’ their surroundings - these being the species that roost in darker habitats such as caves, and those that are most active at night. Obviously, in these conditions, sight is much less effective, and so bats evolved to use high-pitched calls that bounce sound off of surfaces in order to ‘map’ their surroundings and accurately locate prey. Bats are not alone in their use of this technique, as various cetaceans, shrews and a small mammal called a tenrec also use echolocation in a similar way.

The unique adaptations of bats have allowed them to become prolific all over the globe, filling niches that are not oversaturated with competing species, and giving them the opportunity to be highly successful.

Why are bats linked to Halloween?

One theory which may explain the association comes from a Pagan festival called Samhain, where people would light bonfires that attracted large amounts of insects and in turn large amounts of hungry bats. Pagans believed that Samhain (which was celebrated during the end of October and the beginning of November) occurred during a time where the veil between this world and the afterlife was at its thinnest. When the bats started flying erratically around the bonfires, people believed that the bats were wayward spirits travelling between worlds, beginning their association with this time of year.

However - depending on how warm it is - bats are usually inactive at this time of year. They are one of several mammals that use torpor (partial hibernation) to survive through the colder winter months when there is less food availability. This usually begins for bats around November, but in colder years they can start to torpor in October, not coming out until around May.

So, when Halloween comes around and most of us are thinking about bats, ironically they have usually gone into torpor (or are about too) and are less likely to be seen than in the summer months.

Misconceptions

As well as being associated with Halloween, bats have had several other negative misconceptions made about them over the years.

Vampires

The first comes from Bran Stoker’s Dracula. In the book, the titular monster Dracula could not survive in sunlight, had sharp teeth, would sleep upside down, and could transform himself into a bat.

The most infamous characteristic of Dracula (and subsequent vampires) is his diet of human blood, which stems from the fact that some bats do indeed feed on blood. Despite the widespread fear, only 3 species out of over 1,400 across the world actually have this diet, and the animals likely to be targeted will be pigs, cows and birds, which are far more accessible to them than people. All vampire bats are from Central and South America, so in order for the story of Dracula to be accurate, he would need to originate from this region.

So while vampire bats are real and they are the origin of modern-day tales of vampires, in actuality they are small, rare, localised, never kill their victims and consume a fairly small amount of blood per feed.

Witchcraft

Bats are also often associated with witches and ‘evil’ practices, with many people historically believing that bats were witch’s familiars or were used as an ingredient in potions. Many interpretations of satan and demons often possess bat-like wings, leading people to be even more suspicious of these usually harmless creatures.

Disease

The less supernatural threat from bats is the belief that they spread disease, most recently during the pandemic. While it is believed that coronavirus may have its origins in bats, this has not been completely proven, and no bat in the U.K has ever tested positive for it.

It is true that bats can be carriers for disease, however, the only disease found in British bats is rabies. Transmission is rare, being passed via saliva through a bite. It is very unlikely that any British bat species would bite a human unless agitated when being handled, and the appropriate licensing, up-to-date vaccinations and protective gloves are essential before anyone is permitted to handle them.

Bats in the UK - Why should we be interested in protecting them?

There are 18 different species of bats native to the UK, and with 17 of them breeding here, they account for almost a third of our native mammal species. They occupy a diverse range of habitats, being found in woodlands, wetlands, farmland and urban areas.

Bats play an important role in ecosystem management, and though some people may fear them through thinking that they will suck their blood, all our bats are in fact insectivores that help to keep insect numbers from growing too high. The presence of too many insects can have a detrimental effect on agriculture, so by having more bats we can reduce the need for harmful pesticides as they provide a natural pest control.

Bats are also a good indicator of ecological health - it is common practice for ecologists to examine the contents of bat droppings, not just to identify the species they came from, but also to see what insects they have been feeding on. This gives an insight into which insects could be present in a given area, allowing for an estimate of the health of the local ecosystem to be made.

All British bat species, their breeding sites and other roosts are protected by law, and they are all red-listed as at risk of extinction. This means that it is illegal to handle (without a licence), kill or remove bat species anywhere in the UK. There is often a great deal of bat-human conflict during building construction, as many bat species will roost inside dark buildings where they hang freely in void spaces such as lofts or sleep squished under roof tiles.

Therefore, it is a legal requirement that surveys be conducted and the necessary mitigation put in place before any construction or building alterations can occur. This can become very costly depending on the species found, but even so, the protection of bat roosts is vital as we continue to encroach rapidly on their habitat.

Another major threat to bat numbers is the decline in their prey species. With insects being the main food source for bats here in the UK, the use of pesticides in farming and gardening as well as climate change has resulted in a dramatic drop in insect numbers, and 2024 has been a really bad year for bats. The wet spring meant that insect numbers were not at a level where they could support young bats in their first year of life, and so many did not make it to adulthood.

However, charities such as the Bat Conservation Trust are working with local groups across the UK to not only record population numbers but to protect habitats and restore insect numbers to help their food source bounce back.

Bats have historically had negative associations with satanic and evil practices, but in actuality they are small, shy animals that tend to hide away in dark places, are predominantly nocturnal, and take up very little space. They serve a positive function to keep insect numbers from getting out of control and won’t harm people unless handled inappropriately. Bats have great potential to live harmoniously with people and provide vital benefits to our lives, all we need to do is respect them and provide a suitable habitat for them to live in.

If you would like to make a donation towards the conservation of bats in the UK, you can do so here.

Thank you for joining

If you have enjoyed this week’s newsletter, let us know in a comment or share this article so more people can get involved in the conservation conversation. Thanks for reading and see you again next week.